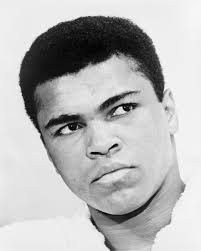

Except for the few astronauts who died in space, no one has ever left this planet alive. So it was with Muhammed Ali, the greatest boxer in history and one of the greatest sportsmen of all times. Ali was a brilliant braggart who inhabited his age and time as a boxer with panache and heroism. Ali was a hero of universal significance, idolized worldwide, not only for his prowess in the ring, but also for his poetry and his politics.

I was in secondary when he visited Nigeria in 1972. The Sunday Times had his picture on the front page with the simple caption: Ali, Beautiful Ali! Those were the days, unlike now, when it was unthinkable to have a secondary school without a library. In those days, we knew what a secondary school library should look like, thanks to the authorities of Ife Anglican Grammar School, Ile-Ife, and our incomparable principal, Prince Israel Adenrele Ibuoye. Our library was always stocked with daily newspapers such as The Times, Sketch, Tribune, Observer, Chronicle, Standard and Herald. There were also magazines: Africa, Drum, Trust, African Films (Lance Spearman and Rabon Zolo), Spear and Readers Digest. We also had China Pictorial, China Reconstruct, Topics, Flamingo, Home Study and Atoka.

In many of these publications, we encountered Muhammed Ali, the great African-American boxer who refused to be drafted into the army to fight in Vietnam. At that time, the United States had intervened in the Civil War in Vietnam with the country divided into two; the North, dominated by the Communists and the South Vietnam dominated by the Capitalist. America supported the South. The North was preaching the gospel of one Vietnam with the backing of China and the Soviet Union.

When America realised that its ally may be defeated on the battlefield, it decided to send in “military advisers.” Young Americans were then drafted to join the army and fight in Vietnam. Ali refused to be drafted in 1966, preferring to endure a prison sentence and a three-year ban from the ring until he was vindicated by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1971. He declared: “I am a black man and I will not help the white man to kill the yellow man!” He said he did not have any problem with the Vietnamese; they did not offend him.

When America realised that its ally may be defeated on the battlefield, it decided to send in “military advisers.” Young Americans were then drafted to join the army and fight in Vietnam. Ali refused to be drafted in 1966, preferring to endure a prison sentence and a three-year ban from the ring until he was vindicated by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1971. He declared: “I am a black man and I will not help the white man to kill the yellow man!” He said he did not have any problem with the Vietnamese; they did not offend him.

He was a man of great resolve who was beaten into shape through the furnace of life experience. He was born January 17, 1942 in Louisville, Kentucky, where he grew up as Cassius Marcellus Clay under the tutelage of a great teacher who taught him boxing and the benefit of endurance. At 22, he shocked the world when he beat the ‘unbeatable’ Sonny Liston and sang that “I float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” He was so different from the brutal Liston. He was young, handsome, poetic, eloquent, fearless, fashionable and dangerously political. He discarded the slave name, Cassius Clay to pick up an Arabic name, Muhammed Ali, joining the Nation of Islam.

In the United States, the 1960s, which was the period of Ali coming of age, was also the decade of the Black Struggle: the march on Washington, the rise and struggles of the likes of Martin Luther-King Jnr, Angela Davies, Elijah Mohammed, Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), Malcolm X (originally Malcolm Little and later el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz), James Forman and Ella Baker. It was also the decade of tumultuous events in America and of painful assassinations: President John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jnr, Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy. It was the decade of the Vietnam War, the riots in American cities and campuses and the triumph of the African-American Civil Right Movement.

For us in Africa, the 1960s was also the decade of freedom and of great, though mostly tainted, heroes. We had Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia who led his country against Italy in the prelude to the Second World War and played a pivotal role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963. 1960s was the decade of Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Modibo Keita of Mali, Sekou Toure of Guinean, Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal, Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Ivory-Coast, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Nwalimu Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia. It was the decade when the great Nelson Mandela stood defiantly before a white judge in Rivonia in South-Africa and proudly received a life sentence along with his colleagues.

For us in Africa, the 1960s was also the decade of freedom and of great, though mostly tainted, heroes. We had Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia who led his country against Italy in the prelude to the Second World War and played a pivotal role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963. 1960s was the decade of Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Modibo Keita of Mali, Sekou Toure of Guinean, Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal, Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Ivory-Coast, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Nwalimu Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia. It was the decade when the great Nelson Mandela stood defiantly before a white judge in Rivonia in South-Africa and proudly received a life sentence along with his colleagues.

Mandela was to achieve his apotheosis in the 1990s.

For us in Nigeria, the decade started on a positive note with the independence of our country from the United Kingdom on October 1, 1960. Our ship of state soon ran into stormy weather: the trial of Obafemi Awolowo, the crisis in the Action Group, the controversial Western Nigeria election of 1965, the coup and counter-coups of 1966, the assassinations of towering figures namely, Sir Abubakar Tafawa-Balewa, Alhaji Ahmadu Bello, Chief Ladoke Akintola, Festus Okotie-Eboh, Major-General Thomas Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, Brigadier Maimalari, Brigadier Samuel Ademulegun, Colonel Ralph Sodeinde and Colonel Kor Mohammed. By the end of the decade, Nigerians were busy killing each other in a vicious Civil War where the leaders of the two opposing armies were less than 40 in age. One old man asked with a sense of pathos:

“This independence we got from Britain, when is it going to end?”

It is good that Ali story ended well. He spent his last moment on June 3, 2016, surrounded by the love of his family and the outpouring of affection from a grateful America and the world. Can we say the same about the sport heroes of Nigeria? Those of our sportsmen and women who were “lucky” to die relatively young such as Taslim (Thunder) Balogun, Oluyemi Kayode, Mudashiru Lawal and Sam Okparaji, had monuments named after them. But how much do we still remember the great men and women who made Nigeria a super-power in world sports once they have left the stage and retired to the humdrums of ordinary life? Do we still remember sport heroes like Hogan Kid Bassey, Dick Tiger, Aloysius Atuegbu, Rasheed Yekinni and Captain Chukwu?

It is good that Ali story ended well. He spent his last moment on June 3, 2016, surrounded by the love of his family and the outpouring of affection from a grateful America and the world. Can we say the same about the sport heroes of Nigeria? Those of our sportsmen and women who were “lucky” to die relatively young such as Taslim (Thunder) Balogun, Oluyemi Kayode, Mudashiru Lawal and Sam Okparaji, had monuments named after them. But how much do we still remember the great men and women who made Nigeria a super-power in world sports once they have left the stage and retired to the humdrums of ordinary life? Do we still remember sport heroes like Hogan Kid Bassey, Dick Tiger, Aloysius Atuegbu, Rasheed Yekinni and Captain Chukwu?

Many of these heroes are still with us, but once they retire, they are mostly consigned to vicious anonymity. Each time I see Segun Odegbami, one of the heroes of the old Green Eagles who brought honour and glory to Nigeria, I ponder that this is a national asset of great value. Mathematical Odegbami, was the magician of the right wing during the Golden Age of Nigeria football when the Green Eagles dominated African soccer. Do we still remember the likes of Captain Christian Chukwu, Best Ogedengbe, Tunde Bamidele, Aloysius Atuegbu, Felix Owolabi, Emmanuel Okala, Henry Nwosu, Godwin Odiye, Adokiye Amiesimaka, Moses Effiong and David Adiele?

Honouring heroes is not idol worship. It is what is expected of a society in need of constant rejuvenation and ceaseless renewal in its journey to greatness. When we remember how Chioma Ajunwa gave Nigeria her first gold medal at the long jump event at the 1996 Atlanta Games, we learn again the meaning of preparation, of endurance, of stamina, and of heroism. It is a new lesson for Nigeria that Muhammed Ali, afflicted with the shackles of illness, crowded with the twilight of old age and finally succumbing to the darkness of death, remains an inspiring figure for the American people, a hero of the Black race, our race. A person, or a nation needs heroes to travel far.

No comments:

Post a Comment